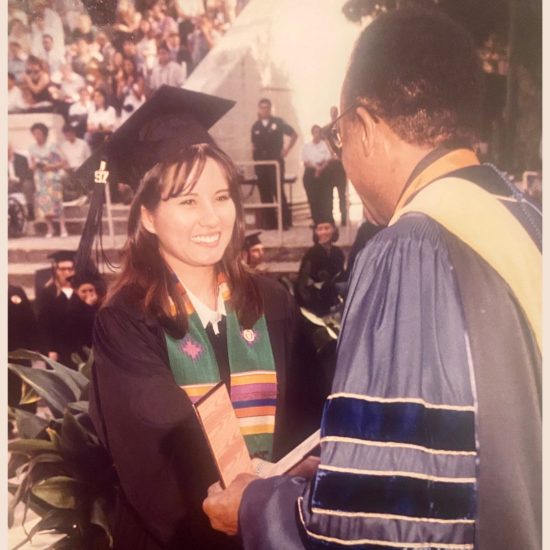

Wendell Dayton in the studio, age 79. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

In the Shadow Hills section of Sunland—a semi-rural Los Angeles municipality where yellow signs warn motorists to “share the road” with equestrians—there’s a dusty lot on the corner of Art Street. Here, one finds an outdoor sculpture garden that could more easily be confused for some perplexing (and perilous) roadside attraction than the plein air studio-showroom of L.A.’s next rising star: 80-year-old Wendell Dayton

Wendell Dayton’s studio view. Courtesy of the artist.

“Petting zoo?” Dayton asks, confused, before directing the mother and child to a nearby horse farm. “At one time this was an orange grove,” he explains. “When I moved here, there were 12 orange trees left, but most of them got old and died.”

Wendell Dayton’s studio shop, 2016. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

Dayton, however, is still standing. Most days, you’ll find him in his on-site metal shop wielding a plasma cutter, chain horse, gantry, or pipe bender with some begrudging help from his new assistant, Brooks. The artist introduces me to some of his favorite mixed-media pets, often with the refrain: “That’s in the show.” There’s The Pair (2016), a wonky weather-vane affair with a stainless steel sugar skull, which is suspended 20 feet in the air; Jenny (2009), a reclining female form hewn from an industrial kitchen counter, who is receiving her lover’s upcycled erection; a funky mobile called Turnstile (2011), featuring arms of pierced steel curves and ripped pipes that mimic the bent oil vessels of Beauty (2004), whose line was borrowed from a woodcut by

Kitagawa Utamaro; and X (1971), a jagged convergence of intersecting planes that represents the final work Dayton made during his days in New York.

Wendell Dayton, Structure, 1975. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

Wendell Dayton, Engine, 1966. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

He got the cash register—40 of them, to be exact, for a buck a piece—from his neighbor. After this first assemblage, Dayton “got in a groove” with some help from Uncle Sam. “I would arrange with my boss to collect unemployment 20 weeks a year so I could work and hang out at the Half Note and listen to Coltrane,” recalls Dayton. The resourceful sculptor also got by with “artist credits” at the lumberyard; siphoning electricity from his downstairs neighbor also helped keep bills down. “I was welding all I wanted to, I could do anything. I didn’t want to leave, but my wife wanted to, so I said, ‘Wait, I’ll go with you.’”

Wendell Dayton, Crescent, 1968. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Permanent collection, LACMA.

Dayton’s work is literally enveloping every crevice of the property. There’s a drained diving pool on the side of the 1939 ranch house that was only used for “a few swims” before assuming its current purpose: a storage area for scraps that may one day yield a sculpture. At the moment, it contains three 10-foot-tall wind chime-like mobiles. As we walk inside, Dayton leads me through a living room-turned-gallery that is filled with discreet, painted sculptures of spliced machinery on top of plinths. (Some have been dedicated to

Wendell Dayton. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

Wendell Dayton, Rising Moon, 1979. Photo by Bryan David Hall. Courtesy of the artist.

After a round of pastries, Dayton goes into an adjoining room and grabs his first-ever sculpture: a small, carved wooden figure—“possibly oak or walnut”—that he made in college, which resembles a pregnant mother, likely a riff on the Madonna and Child.

Though it’s one of the few works that won’t be included in the Blum & Poe show, it does speak to the takeaway Blum hopes visitors will have after getting a deep dive into Dayton’s oeuvre this summer: “That the spirit of an artist is conveyed simply through a daily practice of making work, irrespective of having a professional career.

Courtesy: Here